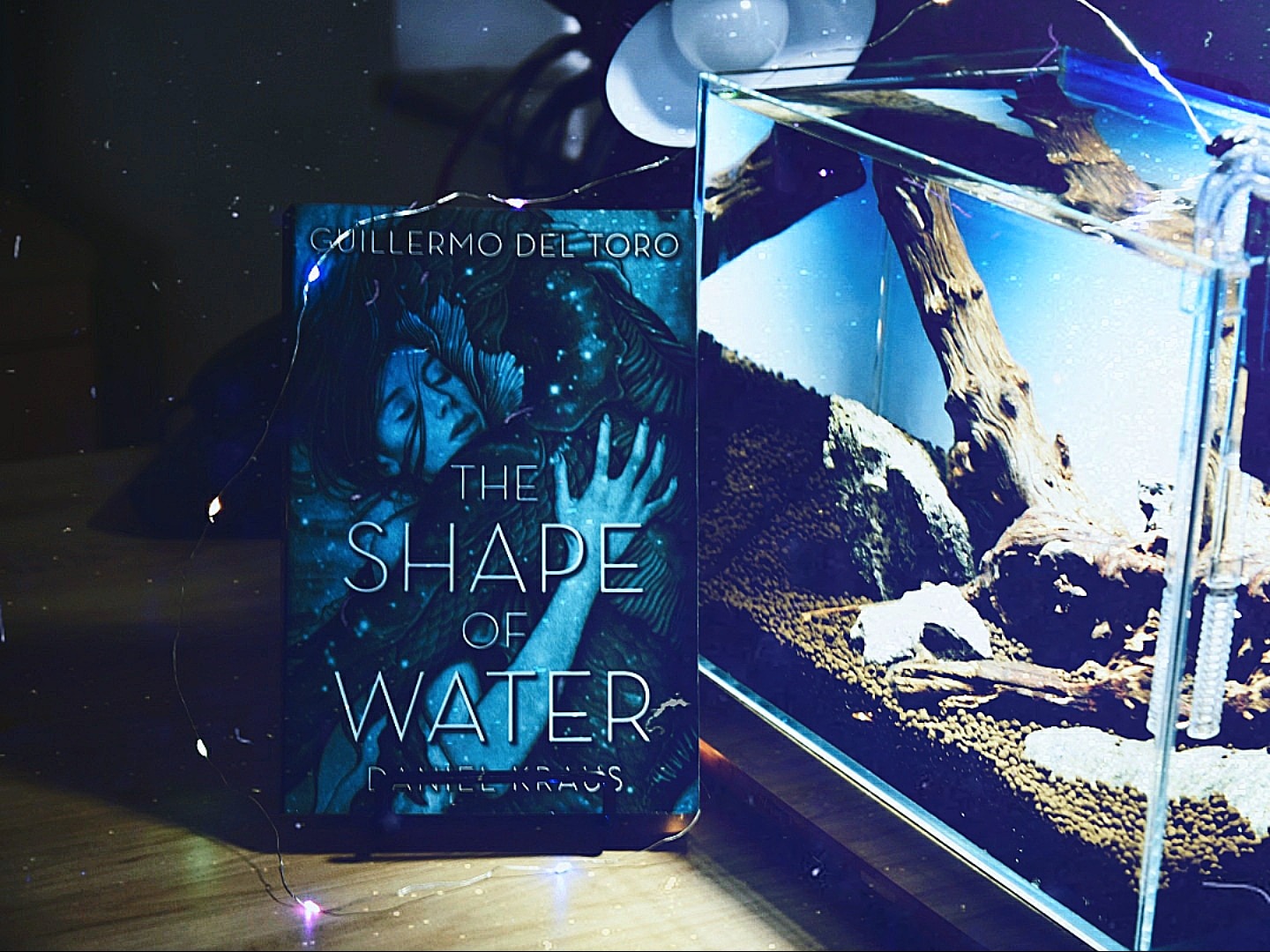

“The Shape of Water” is one of my all-time favorite movies, and I cannot stress enough how deserving it was of the Academic Awards for Best Picture. Therefore, when I knew that this gorgeously haunting and heartbreaking love story was adapted into a novel, I immediately realized that I needed to read it at some point. And the novelized version of “The Shape of Water” certainly did not let me down.

Despite the fact that I have already been familiar with the story, the novel “The Shape of Water” still managed to offer me a brand new and memorable reading experience. This is mostly thanks to the fact that the story was now told in a 300-page literary format rather than a 2-hour cinematic one, which gave much more space for character development and detailed descriptions of important events. One of these events was the beginning of the whole story: how Deus Brânquia – the creature that became one of the main characters – was caught, and how he was portrayed through the beautiful, everflowing prose of Daniel Krauss – the type of prose that came to be signature of the novel:

“Deus Brânquia, at last, rises from the shoal, the blood sun carving the Serengeti, the ancient eye of eclipse, the ocean scalping open the new world, the insatiable glacier, the sea-spray spew, the bacterial bite, the single-cell seethe, the species spit, the rivers the vessels to a heart, the mountain’s hard erection, the sunflower’s swaying thighs, the gray-fur mortification, the pink-flesh fester, the umbilical vine cording us back to the origin. It is all this and more.”

The backstory of Elisa Esposito as a lonely orphan who did not have a true home filled with kindness and understanding growing up was also depicted vividly and heartbreakingly. Of course, we all know from watching the movie that the reason why Elisa always felt that she did not fit in anywhere was because she was destined to be with Deus Brânquia and become one of his kind. However, it was still devastating to see the little girl Elisa not knowing what it meant to exist in someone’s world and not feeling like she was whole except when she was in the cinema, living inside the fantasy the movie screen provided:

“She heard them talk about kissing. One girl said, ‘He makes me feel like somebody,’ and Elisa dwelled upon it for months. What would feeling like somebody feel like? To suddenly exist not only in your world, but someone else’s as well?”

“Here was a place where fantasy overwhelmed real life, where it was too dark to see scars and silence wasn’t only accepted but enforced by flashlight-armed ushers. For two hours and eight minutes, she was whole.”

And there came Deus Brânquia – the only creature in the world who could open up something in Eliza and make her feel whole again, as she was the only being who could connect and communicate with him beyond the level of verbality. A princess without a voice and a jungle God that did not speak the human language. How beautiful a couple they made, as Eliza showed Deus Brânquia the kindness and understanding she lacked so much as a child:

“She knows that she’s been the thing in the water before. She’s been the voiceless one from whom men have taken without ever asking what she wanted. She can be kinder than that. She can balance the scales of life. She can do what no man ever tries to do with her: communicate.”

As their connection and communication grew, so did their love. Hidden beneath a horrifying, scale-filled body who was chained to a pool, Deus Brânquia showed Eliza his gentle, humane, and curious side as he learned the art of signing. And he saw her, her most appreciative, worthy self, her whole being, deserving of love and affection. Everything was described so gorgeously and naturally, like the water surrounding the creature:

“His palm releases the E and his fingers open into a hesitant fan. Elisa nods support and signs G, pointing off to her left. This is considered good signing, but the creature is a novice. His three smallest fingers pinwheel to touch the heel of his hand and he points his index finger directly at Elisa. Her vision spins. Her chest throbs joyfully, almost painfully. He sees her. He doesn’t look through her like Occam’s men or past her like Baltimore’s women. This beautiful being, however he might have hurt those who hurt him first, is pointing at her and only her.”

And Deus Brânquia was a beautiful being, beautiful in the eyes of Eliza – the eyes of a lover who could see both the physical light he emitted and the light within. She was a lover whom he trusted enough to show her his light, light that cast and danced and changed colors as if it was the music front eh vinyl records that they listened together:

“This time she’s got her eyes on the creature, and his light doesn’t only brighten this water, it electrifies it, imbues it with a turquoise glow that shines off the lab walls like liquid fire. The physical objects of table and records slide from Elisa’s awareness as she is reeled toward the pool, her skin blue by reflection, her blood blue, too, she just knows it. Wherever the creature has come from, he’s never heard music like this, a multitude of separate songs so meshed in joyful unison. The water directly around him begins changing – yellow, pink, green, purple.”

I cannot stop experiencing awe with how the love story between Eliza and Deus Brânquia was portrayed. All the touches, all the interactions, all the signings, egg-plays, and fingers curling, they were precious and possessed a certain amount of poetry that made the already dreamy story even dreamier. How much chemistry they had for each other, how much love and rare connection they formed together, just by the touch of hands. And this connection transformed Eliza from an outcast janitor girl into a woman who was deeply in love:

“The touch of his hand, rare but thrilling, when he plucks eggs from her palm. The one time she dares hold nothing at all, and still he reaches out, draws his claws softly down her wrist, curling his hand into her palm as if enjoying the pretend-egg play, and letting her close her fingers around his, for that instant making the two of them not present and past, not human and beast, but woman and man.”

“She gazes into the creature’s eyes, still bright underwater, and listens to the soft bubbling of his breath. He blinks, a greeting. She unfolds an arm and fins her index finger through the water until it touches the back of his hand. Unexpectedly, he rolls the hand over so that she is touching his palm, her finger the single stamen of a huge, dewy, unfolding flower. Now she listens for her own breath, but hears nothing. Hands are how the two of them talk, but this? This is a touch. Elisa pictures the woman on the bus, how rigidly she sat, touching no one. An absence of fear, Elisa realizes, can be mistaken for happiness, but it isn’t the same thing. Not even close.”

And when they made love, it was even more transformational than what Eliza could ever imagine. The act of sex, for both of them and especially for Eliza, was not just two bodies joining together. It was also the celebration of the precious connection between them, culminating in the transfer of knowledge about pain and pleasure, and about the whole world that ever existed. How I wish I could one day experience this type of love making, this type of connection going beyond the physical realm to enter a place of higher realization that permits us to experience the whole world all at once:

“The effulgence of the theater lights eking through the floorboards and plastic are overwhelmed by the creature’s own rhythms of crystalline color, as if the sun itself is beneath them, and it is, it has to be, for they are in heaven, in God’s canals, in Chemosh’s slag, every holy and unholy thing at once, beyond sex into the seeding of understanding, the creature implanting within her the ancient history of pain and pleasure that connects not only the two of them but every living thin. It is not just him inside her. It is the whole world, and she, in turn, is inside it.”

Besides detailing the story of the main characters, “The Shape of Water” also allowed the side characters space to have their own stories and struggles told. One of them was Lanie Strickland – the dutiful wife of Richard Strickland who suffered from PTSD after all the secret and brutal jobs he had done following his boss’ orders. In the movie, Lanie was briefly portrayed as the exemplary trophy wife of the 1960s, whose only job was to take care of her family and please her husband sexually without having any say about her own life.

Here in the book, readers can get more glimpses into Lanie’s mind and her journey to develop her own agency and take back control over her life, starting with having her own job. We can all agree that the 1960s was not kind, understanding, and forward-thinking to women, whether it was a mute girl who had to settle with being a janitor like Eliza, or a seemingly happy woman of a model nuclear family like Lanie. Both had suffered under the hands of men, and both had to grapple with the iron hold that the patriarchy had on the females of the society until they found enough strength to break free and to act on their own free will.

Then we have Giles – the 60-year-old closeted gay artist who was Eliza’s best friend. The society at that time was also not kind and accepting to people like Giles. Therefore, he had to hide his own sexuality and conform to what the society wanted to see from a man like him, and also to what his client wanted to receive from an easily bullied freelance artist. So Giles allowed himself to be devalued and disrespected, to produce mediocre advertising illustrations that did not even show a glimpse of what he could be as a talented artist. This made what Lanie – through a beautiful twist of fate which led her to meet Giles – told Giles even more thought-provoking, as they reflected back on their current situations and their quests to realize their own self worth:

“‘You deserve better than this. You deserve people who value you. You deserve to go somewhere where you can be proud of who you are.’

The voice, Lainie realizes, feels sovereign from her because it’s not only speaking to Giles Gunderson – it’s speaking to Elaine Strickland. She deserves better; she deserves to be valued; she deserves to live in a place where pride is not an exotic gift. Once more, the young wife and doddery gent are one and the same, stamped as deficient by people who haven’t the higher ground to make the accusation. Klein & Saunders is a start but only that: a start.”

At the end of the day, “The Shape of Water” brought to the papers a uniquely beautiful love story that went beyond the romantic aspect to reach deep into other societal issues and struggles. It did what the movie version could not do: give characters more chances to be heard, understood, empathized, and honored. Coming back to the beauty of the haunting love story that was the source of all magical feats, the book closed out with unforgettable words that left a lingering mark in readers, as Eliza sank deep down into the water and became her lover’s kind:

“She reaches out to him. To herself. There is no difference. She understands now. She holds him, he holds her, they hold each other, and all is dark, all is light, all is ugliness, all is beauty, all is pain, all is grief, all is never, all is forever.”

Final verdict: 9/10. I got chills all over my body reading this book.